2024/25 Impact

WHAT WE’RE MADE OF

Scroll down...

Scroll down...

Throughout this report, you’ll find the human story interwoven in every section. Because it’s people making this happen – all of it. This is population-level involvement driven by a desire to create generational change and define our city as a place where nature and people thrive together.

That collective commitment is what we’re made of – and it’s what this report: What We’re Made Of reveals.

If you are interested in learning our methods and approaches, the Innovation section reveals how we’re pushing boundaries and finding efficiencies with detector dogs, new technologies, and biosecurity approaches that are changing what’s possible in urban conservation.

If you want to be inspired by what people-centred conservation can achieve, dive into Impact to see how eliminating rats and mustelids has not just strengthened our native bird populations, but strengthened our collective sense of place and purpose.

If you are wondering how we are advocating and planning to keep scaling. Leadership and Next Five Years shows you the grit and passion we have to ensure this work continues and expands.

After another big year we’ve proven our mettle, positioning Wellington as the urban exemplar showing New Zealand and the world what’s possible.

Ehara taku toa i te toa takitahi engari he toa takitini

Our strength does not come from ourselves alone, our strength derives from the many

Every day I am reminded (sometimes as early as 4am) of the explosion in native birdlife on Wellington’s Miramar Peninsula now that rats and mustelids have been removed.

Birdsong is increasingly the sound of the Capital as we advance from the waterfront and the CBD across the suburbs to Island Bay. We are now actively planning Phase 3: an equally ambitious 2700-ha third front on Wellington’s urban fringe that will include Brooklyn up to Zealandia’s boundary, extending from the city to the south coast.

Wellington has become a national and international exemplar of the successful elimination of invasive rats and mustelids that do such damage to native wildlife that has no defences against introduced species. Our claim to being the only capital city on the planet, perhaps the only city, where biodiversity is increasing has not been challenged. That is only possible through the unceasing efforts of a dedicated staff and hundreds of volunteers. We appreciate that enormously and are looking to recruit even more volunteers, as much as doubling the numbers already regularly patrolling traps, bait stations and cameras.

The sudden axing of the Predator Free 2050 agency established by the Key Government and its absorption into the Department of Conservation has caused some concern and uncertainty. A project framework review is under way and while DOC has been supportive of the predator free vision, as yet there is no budget allocation. Also of concern is that of the substantial sums being raised by the International Visitor Levy – over $200 million in the coming year – that were earmarked for conservation and tourism infrastructure and projects, more than half is being diverted into government coffers.

Even so, our resolve is undaunted. There are challenges ahead and we need continuing support to meet them. We continue to work closely with our friends at Capital Kiwi and Zealandia under the emerging concept of an encompassing Wild Wellington banner. As this report shows, our work is having a profound impact on Wellington’s wellbeing, for both its human and its wildlife populations.

— Tim Pankhurst

Chair, Predator Free Wellington Ltd

Conservation at this scale needs backing at every level.

find your way to CONTRIBUTE – from monthly giving to major gifts

When we talk about eliminating rats, stoats, weasels and possums, we’re not just counting bait stations or celebrating catches. We’re investing in something much bigger – a vision of what urban life can become when we align our actions with what matters most.

Predator Free Wellington is proving that cities don’t have to choose. Not between people and biodiversity. Not between what’s practical and what’s possible. We’re demonstrating that people and nature thrive together – and getting that right creates benefits that ripple far beyond what we initially imagined.

We’re building:

Tūī. Photo credit (©) Tim Sutton

Tūī. Photo credit (©) Tim Sutton

The elimination of invasive rats, stoats, weasels and possums is the output – a necessary step, but not the destination. The impact is what comes next: a predator free capital city and the multifaceted outcomes that brings for our people, our nature, and our role in the world.

This is about showing what’s possible. Wellington is writing the playbook for how urban communities can reverse biodiversity decline at scale. We’re proving that cities – where most of us live – don’t have to be biodiversity deserts. They can be thriving ecosystems.

And when we get this right, something remarkable happens: nature doesn’t just bounce back. It keeps building, year after year.

On the Miramar Peninsula, we’ve demonstrated that nature can not only recover but continue to flourish when we create the right conditions.

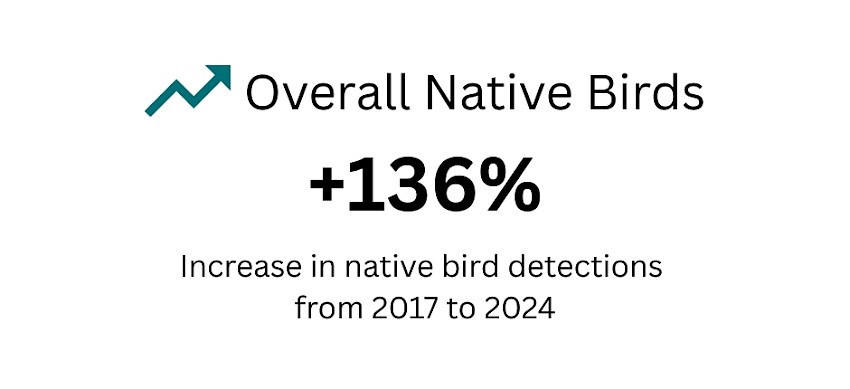

When we eliminated the last rats, stoats and weasels from the peninsula in late 2023, native bird numbers had already surged – a 91% increase since 2017.

But here’s what we’ve learned since: the recovery doesn’t plateau.

Native bird detections have now increased by 136% since 2017, while introduced bird species have declined by 14%.

Remove invasive species, and nature doesn’t just stabilise at a new normal – it keeps building momentum.

Each year predator free adds to the previous year’s gains. Breeding success compounds. Populations strengthen.

As native bird populations increase, they naturally outcompete introduced species for food and habitat. We’re not removing introduced birds – native species are reclaiming their territory, a pattern seen at Zealandia, Kapiti Island and other predator free sites. When invasive predators are removed, native birds have a competitive advantage. Made with Flourish

Click on each bird to learn more.

These results don’t happen by accident – they’re funded

BE PART of scaling this success

Each Wellington suburb has its own character. We keep residents updated with the number of houses involved and rats caught – a little friendly competition between neighbouring suburbs.

This is what’s possible when communities invest in nature

Explore partnership opportunities with us

While the formal bird monitoring is important and helps us understand long term trends, citizen science observations show us which species are arriving next, and where they’re choosing to settle.

Through eBird and iNaturalist, peninsula locals have contributed over 8,800 bird observations since 2017. These observations capture what annual surveys can’t: the rare, the nocturnal, the unexpected.

Residents have documented additional native species – korimako/bellbirds (26 sightings, mostly around Mt Crawford and Scorching Bay), kākā (six sightings), kākāriki/red crowned parakeets (20 sightings across northern and eastern areas), ruru/morepork (63 observations in forested areas) and one koekoeā/long-tailed cuckoo.

Kārearea. Photo credit (©) Michael Szabo.

Kārearea. Photo credit (©) Michael Szabo.

Kārearea/NZ Falcons have been recorded 288 times by citizen scientists across the peninsula – from native forests to suburban backyards – with two breeding pairs now established in the Shelly Bay and Worser Bay areas.

![]()

The IUCN Red List identifies invasive species as one of the major causes of biodiversity loss globally. Sixty-one percent of the world’s bird species are in decline. Against that backdrop, what’s happening in Miramar Peninsula and wider Wellington takes on a larger significance. By demonstrating that we can eliminate invasive species at scale, we’re contributing to the UN Sustainable Development Goal 15: Life on Land, which calls for protecting, restoring and promoting sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems. The peninsula is proof that urban biodiversity recovery is possible. What we’re learning here in Wellington can inform conservation efforts in cities worldwide.

Wellington is writing the playbook for urban conservation worldwide.

INVEST in proven OUTCOMES

A kākā on a deck in Wellington, living its best life. Video credit: Jacki Condra

The most significant change isn’t always the one you notice immediately. For Miramar residents, the transformation came with a delayed realisation: we didn’t know what we were missing until it returned.

Between July 2023 and April 2025, we collected and analysed stories from diverse stakeholders involved in Phase 1 of Predator Free Wellington on the Miramar Peninsula. The stories have revealed not just wildlife recovery, but the emotional experience of witnessing biodiversity recovery. When a volunteer describes: “we’re seeing kārearea, which we never saw before. Even the lizards are making a comeback,” these narratives capture both the ecological facts and the personal meaning of change. Similarly, when residents reflect that “people feel connected to something bigger,” we see how the project has shifted from abstract appreciation to concrete action and connection – insights that numbers alone could never tell.

“Before the eradication, I never thought this place lacked biodiversity – it wasn’t a desert – but now that it’s flourishing, I reflect back on what wasn’t there. I didn’t think about what we were missing in terms of the dawn chorus. There were a couple of kererū (wood pigeons) up the tracks, but nothing like what we see today.”

Pete, resident and previous board chair

The highlighted stories below were selected by our review panel as representing some of the significant changes observed throughout the project. These stories provide powerful firsthand accounts of transformation across different themes and stakeholder perspectives.

Want to be part of what cities can become?

Wellingtonians are defining what cities can become, one trap at a time. Get amongst it – because individual actions from lots of people create the big outcomes we’re seeing

Phase 1 was world-first territory – our R&D project. We proved eliminating rats and mustelids from urban landscapes was possible.

Phase 2 and beyond is a different challenge: refining what we’ve learned, hunting for the sweet spot where cost, speed, and effectiveness align.

We’re learning new ways to manage biosecurity – keeping rats and mustelids out once they’re gone. We’re testing new technology and approaches that reduce labour while maintaining effectiveness.

Efficiency isn’t just about saving money – it’s what makes scale possible. These gains compound, turning proof of concept into a replicable model.

The case studies below share some of our learnings from the past year.

Photo credit (©) Tim Sutton

Photo credit (©) Tim Sutton

THE CHALLENGE

Every operational improvement we make compounds across thousands of properties. If we can reduce the number of services needed to clear each project zone, that scales into weeks saved across suburbs.

OUR APPROACH

We completely flipped our processes this past year. Traditionally, detector dogs came in at the end – a final sweep to find any remaining rats we’d missed. Now our detector dog team (Sally Bain and dogs Rapu and Kimi) survey zones before our field team arrives.

This give us a strong early indication of where rats are living, feeding, and moving – sometimes revealing just how ratty certain areas are, particularly older housing with countless nooks and crannies offering rats hiding spots and food sources.

Dog detection information goes straight into Trap.NZ, giving our field team a detailed picture before they place a single device. They can see rats’ favoured locations, movement pathways, food sources and then target those spots.

It’s about multiple layers and checks, not multiple months of time and dollars.

This year we refined our dog-detection system to three categories. ‘Active’ shows den sites, ‘Passive’ shows recent rat presence, but no activity and ‘Tracking’ reveals rats on the move.

THE IMPACT

The numbers tell the story. We compared Phase 2’s low risk areas in Newtown against Phase 1’s Miramar flats – similar suburban habitat, similar starting rat activity. In Miramar flats, we serviced the area weekly for six months, with devices averaging 20 visits each before areas moved into monitoring. At roughly 10 minutes per device visit, that’s 200 minutes of field time per device.

In Newtown, some sections moved into monitoring after just three services. That’s an 85% reduction in device visits – a valuable efficiency gain in both time and cost.

We also decreased servicing frequency. Some Newtown sections went straight to fortnightly visits instead of our usual weekly schedule for 3-4 weeks, and we adjusted device spacing based on what the dogs told us about actual rat presence.

Compare this to steeper, vegetation-heavy zones in Mt Victoria, where dog surveys indicated high rat presence. We responded by increasing device density, and some of these areas only required 6-9 services before moving into monitoring.

This isn’t just about speed. It’s about precision. We’re placing devices where rats actually are, rather than blanketing entire areas and hoping for the best. We’re reading the landscape through the dogs’ and our team’s expertise, making real-time decisions about device density and servicing frequency based on actual rat presence, not assumptions.

This is made possible by supporters like you

LEARN HOW to help

Installing the H2Zero units in Mt Victoria

Installing the H2Zero units in Mt Victoria

THE CHALLENGE:

We need a range of effective tools in our kit. Standard bait stations work well for most situations, but require fortnightly visits to refresh bait and check activity. As we scale this work across Wellington, we need additional tools that can eliminate rats more efficiently – whether that’s extended servicing intervals, better performance in difficult areas, or solutions for sites where standard devices aren’t suitable.

OUR APPROACH:

In partnership with Zero Invasive Predators (ZIP), we trialled their H2Zero units in an urban environment. ZIP wanted to see how their technology would perform in Wellington’s conditions. The H2Zero units slowly release Rodenthor Gel (a NZ registered brodifacoum bait) over extended periods, keeping bait fresh and available without constant human intervention. This early prototype we trialled can run for three months between services instead of the usual fortnight – an 85% reduction in servicing visits.

We trialled ZIP’s bait tunnels fitted with H2Zero units in Mt Victoria. We installed trail cameras throughout the area to monitor the resident rat population – starting four weeks before baiting to establish a baseline.

We trialled ZIP’s bait tunnels fitted with H2Zero units in Mt Victoria. We installed trail cameras throughout the area to monitor the resident rat population – starting four weeks before baiting to establish a baseline.

Bait stations were laid out on a 50 × 50 m grid, with additional stations added later in rat-prone habitats. Initially we checked these H2Zero units every 4 weeks, then extended this to 10+ weeks as we refined the approach.

WHAT WE LEARNED:

The trial revealed what worked, what needed fixing, and what matters most for effective rat elimination:

WHAT THIS MEANS:

The H2Zero unit adds another tool to our kit. When functioning effectively, these devices can remain in the field for up to three months, continuously dispensing fresh bait – an 85% reduction in servicing visits compared to traditional fortnightly schedules. This could significantly reduce labour costs, allows us to cover a much larger area with our field team, and help us scale faster across the city.

New technology can help drive efficiency towards predator freedom, but it’s not a plug and play. Success depends on combining new tools with field knowledge, monitoring, and willingness to adapt. The partnership approach – working directly with innovators like ZIP to test technology in urban conditions – accelerates learning for everyone. But it can be frustrating at times too, when the technology doesn’t quite work as planned: so be prepared.

WHAT’S NEXT:

We continue to use our standard ‘Pelgar’ bait stations for the bulk of our network. But now we have some new options which could help us scale faster across the city.

With H2Zero’s low service frequency and constant bait availability, this tool could be particularly useful for biosecurity – as a way to protect the gains we are making without overburdening our field team.

ZIP is currently refining a second prototype of the H2Zero which will be able to dispense bait over six months, reducing servicing costs even further.

The real win here is flexibility and options. As we refine our understanding of where each tool delivers the most value, we’re building a toolkit that’s both effective and affordable – crucial for any project looking to replicate our work.

Monitoring camera footage showing a rat entering a ZIP bait tunnel

Help us grow our impact

SUPPORT our next chapter

THE CHALLENGE

How lean can we make biosecurity monitoring while still catching rats early?

This past year, we faced competing pressures: we needed to protect the gains in Miramar while maximising our time and budget for advancing into Phase 2. We also needed rapid, accurate detection methods that could cover ground quickly when rat activity was sparse. A rat incursion in Maupuia gave us an unexpected – and costly – answer about what doesn’t work, pushing us to innovate across our entire biosecurity approach.

Think of it like the Swiss cheese model: each detection method has holes (gaps in coverage, times when it misses things). If you only use one method, or space devices too far apart, the holes line up and rats slip through undetected. We could theoretically put devices everywhere and eliminate all gaps – but that’s not financially sustainable. The challenge was closing enough holes to catch rats early, using the minimum number of devices and methods that still worked. Smart coverage, not total coverage.

We tested this the hard way.

Tim installing a rat-detection camera in a tunnel in Miramar. Complex urban landscapes like these make predator elimination challenging and innovative. Photo credit (©) Tim Sutton

Tim installing a rat-detection camera in a tunnel in Miramar. Complex urban landscapes like these make predator elimination challenging and innovative. Photo credit (©) Tim Sutton

WHAT HAPPENED:

In the past 12 months, we deliberately thinned our Miramar biosecurity network to see if we could make it cheaper and faster to maintain. Trail cameras were reduced from one per hectare to one per 5 hectares (or less), checked every 4-5 weeks instead of monthly. The goal: free up resources for Phase 2 clearance work while still protecting Miramar.

In May 2025, a public sighting tipped us off to rat activity in Maupuia. We responded immediately with dog detection, traps, bait stations, chew cards, and additional cameras. What we found wasn’t encouraging: ship rats had already invaded, bred, and spread across approximately 40 hectares. It took three months of intensive work to eliminate them – 39 rats in total.

The network had been too sparse for the high-risk urban areas. We’d found the wrong side of the efficiency line.

OUR APPROACH:

The Maupuia event clarified what we needed: not just more devices, but smarter deployment using multiple complementary detection methods, each with different strengths and costs:

Strategic placement using historical data:

Rather than simply spacing devices evenly across the landscape, we now use heat mapping of historical rat activity to inform where we place our monitoring devices. This data-driven approach means cameras and chew cards go where rats are most likely to appear – near boundaries, along movement corridors, and in areas with previous detections. When you have fewer cameras, placement becomes absolutely critical. A poorly placed camera means missing a population until it spreads to the next device, 5 or more hectares away.

The results were immediate. Our optimised cameras spotted rats five times in places where we had previously never seen rats across three years of monitoring.

Innovating Dog Detection:

We’ve systematised how we use our detection dog team to maximise efficiency. We created biosecurity check areas with inspection rotations – monthly, quarterly, or semi-annually – based on habitat quality and historic rat data. These rotations adapt as activity patterns change. Within each area, specific points are chosen based on historical detections and suitable rat habitat, making detection more targeted and effective.

A map of dog detections of rats in Rongotai (click to expand). The blue lines are Sally’s GPS tracks with the dogs. Orange icons are passive dog detections, where there may have been old activity.We’ve also automated dog detection data and dog line tracking in our field map system. The field team can now view this information in real time, and data flows automatically to and from the field and office without manual data entry. This has eliminated daily manual data imports and extraction tasks for our Eradication Technical Officers (ETOs), saving significant time while improving accuracy.

A map of dog detections of rats in Rongotai (click to expand). The blue lines are Sally’s GPS tracks with the dogs. Orange icons are passive dog detections, where there may have been old activity.We’ve also automated dog detection data and dog line tracking in our field map system. The field team can now view this information in real time, and data flows automatically to and from the field and office without manual data entry. This has eliminated daily manual data imports and extraction tasks for our Eradication Technical Officers (ETOs), saving significant time while improving accuracy.

We then matched monitoring intensity to risk level:

Efficiency gains:

WHAT’S NEXT

We’re rolling this refined system out across all cleared areas and training volunteer specialists to run biosecurity monitoring in their zones. This shifts us from elimination mode to biosecurity mode – and proves the model can sustain itself.

For dog detection specifically: We’re conducting statistical analyses on Sally’s detections to evaluate the accuracy of different detection types (active, passive, tracking). Based on these results, we’ll finalise response protocols that vary depending on the detection type – ensuring we respond appropriately to different levels of detection certainty.

The Maupuia incursion was initially disappointing for our team, but it gave us invaluable data. We now know where the line is between too sparse (risky) and appropriate coverage (efficient and effective). That knowledge feeds into the collective learning toward Predator Free 2050.

WHY THIS MATTERS

This impact runs on community support

your donation directly funds traps, training, and the tech making wellington predator free. PLEASE GIVE NOW

Leadership in conservation isn’t just about what we achieve within our own project boundaries – it’s about changing the systems that make lasting change possible.

This past year, Predator Free Wellington has stepped into a broader role: demonstrating what urban conservation looks like at scale, mobilising a movement that extends far beyond Wellington, and ensuring the lessons we’re learning reshape how Aotearoa and the world approach conservation in cities.

Our leadership shows up in multiple ways – from bold public campaigns that connect identity to action, to sharing economic analysis that reframes conservation as an investment rather than cost, to international knowledge-sharing that gives others the tools to follow.

Through it all, we’re building something designed to sustain itself, proving that community-led conservation delivers lasting change.

Funding remains the most critical aspect of achieving our goals. We currently face a $1.75 million annual funding shortfall, largely due to decreased government funding from the upcoming financial year. While we continue to strongly advocate across all funding channels, we’re also willing to think creatively and try new approaches.

In June 2025, we launched a public fundraising campaign that operated outside our usual mode – but represents exactly the kind of innovation we need to embrace.

The ‘Call Yourself a Kiwi’ campaign emerged from a partnership with Wellington agency 81 and was hosted by PF2050 Limited and then the Predator Free NZ Trust, on behalf of all the PF2050 Landscape Projects across Aotearoa New Zealand.

The campaign’s central question cuts to the heart of our national identity: if there were no more kiwi, could you still call yourself one? Building off the premise that we’ve been taking our namesake and other native taonga for granted for too long, we challenged companies and everyday New Zealanders to give a dollar (or more!) for the right to keep calling themselves a Kiwi – supporting our work to create environments where the kiwi and all its mates can survive, and thrive.

Karen O’Leary and Dan Henry introduce the ‘Call Yourself a Kiwi?’ campaign

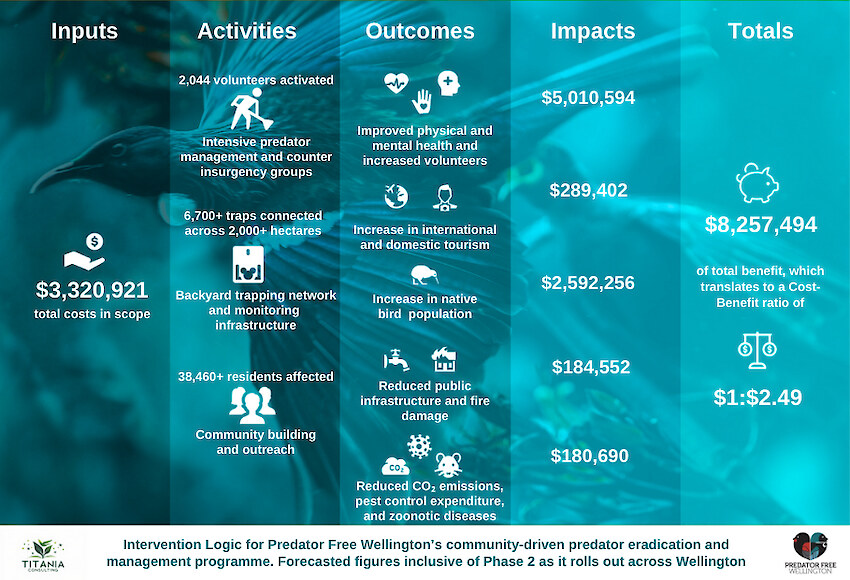

Conservation work is often framed as a cost – something worthy but difficult to justify against competing priorities. We’re working to change that by demonstrating that predator elimination isn’t just an environmental expense, it’s a sound economic investment with returns that benefit everyone.

In 2025, we commissioned an independent economic assessment to quantify the full value of our work. The results show a return on investment of up to $2.49 for every dollar invested – and these returns are expected to grow over time. During Phase 1 on the Miramar Peninsula, the ROI was $1.29 per dollar. As we expanded into Phase 2 across a larger area, that return nearly doubled.

These aren’t abstract numbers. They represent real value generated through job creation (42 full-time positions through Jobs for Nature funding), substantial volunteer contributions (55,000 hours annually, worth approximately $2 million), avoided costs from pest damage to infrastructure, and innovation that has reduced operational costs by up to 75% per hectare compared to other methods. Our advances in detection technology alone have cut previous labour requirements by 30%.

The assessment also captures social co-benefits that have quantifiable monetary value: improved community cohesion, enhanced personal wellbeing through nature engagement, and public health gains from removing disease-spreading pests. Looking ahead, we expect additional economic benefits including tourism growth, enhanced property values, and continued public health improvements.

Everyone gets to enjoy the benefits. Predator free neighbourhoods mean safer native wildlife, healthier communities, reduced infrastructure damage, and stronger social connections. By demonstrating these returns to funders and stakeholders, we’re reframing the conversation from ‘conservation for conservation’s sake’ to ‘conservation as smart investment in community well-being and economic prosperity.’ It’s about showing leadership by being transparent about value creation and making the case for sustained investment in outcomes that matter to all Wellingtonians.

The return on investment in urban conservation is undeniable

PARTNER WITH US to prove what’s possible

Many conservation projects struggle with the same trap: they can never leave. Success creates dependency – the more you achieve, the more resources you need to defend those gains forever.

We’re breaking that cycle through genuine partnership with volunteers, and it’s one of the most important aspects of our leadership.

We can’t be here forever, and we shouldn’t need to be!

Our model is deliberately designed with an end date. Once we’ve cleared an area, we need people who know that land intimately – who walk it daily, who are passionate about their neighbourhood, who understand what they’re protecting and why it matters.

What we’re building

Our huge network of volunteers help us move forward with our project and give us the security to defend areas when we leave. This year we’ve opened new areas (Truby King Park) for volunteers to manage, which expands part of our Phase 2 buffer.

What’s involved with volunteering?

We run workshops where we train and upskill new volunteers. They’re shown how to use our traps and bait stations, how to detect signs of rats and taught about rat behaviour. We then assign them a line of stations to check and from there, they work independently!

Each area has a group lead who manages and motivates their team. These skilled community leaders are running teams of experts who watch for rats sneaking into areas we’ve cleared. These eyes and ears on the ground are part of our exit strategy, giving us confidence in the long-term success of our project.

Our Phase 2 buffer is manged entirely by volunteers. The buffer runs from Ōwhiro Bay up through the green belt to Mt Cook and through to the waterfront, marking the boundary of Phases 2 and 3. Volunteers are involved in monitoring and maintaining 1000+ devices, ensuring the buffer’s effectiveness in preventing rat invasion from the west.

How big an impact do volunteers have?

It’s huge! Our team of 40 volunteers work around Miramar Peninsula, checking traps, bait stations and cameras. In our Phase 2 buffer, we have 124 volunteers managing 1,018 traps and bait stations, in nine zones, protecting 250 hectares.

This impact doesn’t include the more than 2,200 volunteers checking traps in their backyards and in reserves across Wellington. The dozens of community groups make a huge difference reducing rat numbers.

Learn more about our community heroes and find your local trapping group.

What’s next?

We’re evolving how we work with volunteers – we’re aiming to double our numbers in the next year. The kinds of volunteer tasks are also changing. More of our volunteers will move from generalists (who mainly check traps) to specialists. These specialised roles will focus on biosecurity: they’ll check chew cards and cameras, or train other volunteers. We’re currently rolling out this work which we’ll explain fully in the next report.

We are now also working closer with Predator Free Miramar (PFM) volunteers. Their amazing work since 2017 helped make the peninsula predator free. PFM founder Dan Henry was ready to step back a little from his organising role and the PFW crew now work in step with our other trained volunteers.

Dan’s highlights of the year include seeing more kākāriki, sharing knowledge with other groups around the country, and being a finalist for Sustainability Leader of the Year 2025 – all great chances to show the impact of PFM’s work.

The world is watching Wellington.

Our urban blueprint – documenting five years of hard-won knowledge about removing rats, stoats and weasels from dense urban environments – is being shared with similar projects around the world. It’s a playbook that didn’t exist before we wrote it.

We regularly field queries from conservation projects across continents. How did you secure community buy-in? What does your device network look like? How do you manage biosecurity? These are questions from people trying to replicate our work in their cities.

In October 2025, we represented Wellington at the IUCN World Conservation Congress in Abu Dhabi – the largest gathering of conservation professionals in the world, with over 10,000 attendees from 140 countries. We showcased Wellington’s model as proof that urban communities can reverse biodiversity decline at scale. Our approach – people centred, nature-centred, scalable – is inspiring cities worldwide.

International media coverage continues to amplify our story. Because what’s happening here matters beyond Wellington. If we can do this in a working capital city of 212,000 people, other cities can too.

This map shows some of the places our work and knowledge is shared. We work with similar projects and share our story with global audiences through media coverage.

In a year of significant transition – with the disestablishment of Predator Free 2050 Ltd and its integration into Department of Conservation (DOC) – we’ve worked closely with other predator free projects and the Department to ensure Wellington’s pioneering work remains recognised and supported. We have lobbied for Wellington to be acknowledged as the urban exemplar in the national strategy, ensuring our work is understood, prioritised, and supported for the long term.

This kind of advocacy work isn’t glamorous, but it’s essential leadership. It ensures that the systems supporting predator free work are resilient, that our work isn’t isolated or vulnerable, and that what we’re proving here can scale beyond Wellington. Even as structures around us shifted, we maintained momentum, stayed visible, and continued demonstrating what’s possible when communities lead.

As world-first pioneers, we carry a particular responsibility. What we’re demonstrating matters beyond Wellington. In a world searching for hope, we’re showing that nature and cities can thrive together – and we’re doing it in ways that put people first, embrace equity, and prove that grassroots action at scale can deliver extraordinary results. That’s the kind of leadership that changes what people believe is possible.

This is just the beginning

BACK THE WORK that’s rewriting what cities can be

What we’ve achieved on Miramar Peninsula (Phase 1) was just the beginning. The next five years will push the boundaries of urban predator elimination, tackling environments no one has attempted at this scale – from fully-operational zoos to landfills, from the precious halo around Zealandia to Wellington’s steepest terrain in the south and west. Each phase unlocks new possibilities and proves what’s achievable in complex urban landscapes.

Phase 2 (completing 2026) marks a significant shift in our operation. This year we encountered our first possums, meaning we’re now working with all four target species – rats, stoats, weasels and possums. We’ve taken on management of possum control in the Brooklyn/Mt Albert area, work that was previously delivered under the GW/WCC agreement. This shift has freed up WCC funding to strengthen possum control networks along the Skyline track. This is a good example of how our work delivers greater value for both city and regional councils, enabling more strategic impact on shared conservation outcomes.

This phase also takes us into uncharted territory: making Te Nukuao Wellington Zoo rat free. We began with baseline monitoring and detector dog surveys to understand the existing rat population. The Zoo’s investment in their own pest control gives us a head start. Now, with devices installed and close collaboration underway, we’re navigating the complex considerations of eliminating rats from an operational zoo – balancing animal welfare, staff and visitor safety, and conservation outcomes in ways never attempted before.

We’re also tackling dense urban landscapes like Hataitai, the green belt, and Island Bay and Ōwhiro Bay – complex environments that will test and prove our urban predator control model. We’ve already cleared Miramar, Kilbirnie, Lyall Bay, Rongotai, Hataitai (a total of more than 1,500 hectares) and reached the CBD.

Phase 3 of our projectPhase 3 gets exciting. Most significantly, we’re creating a protective halo around Zealandia, expanding the sanctuary’s halo footprint fivefold – from 225 hectares to encompass Te Kopahou Reserve’s 1,200 hectares.

Phase 3 of our projectPhase 3 gets exciting. Most significantly, we’re creating a protective halo around Zealandia, expanding the sanctuary’s halo footprint fivefold – from 225 hectares to encompass Te Kopahou Reserve’s 1,200 hectares.

As our work expands into Capital Kiwi’s territory, the potential for synergy grows. Imagine Capital Kiwi, Zealandia, and Predator Free Wellington’s efforts converging – creating an interconnected predator free landscape where kiwi and all of our most precious native taonga (native wildlife) can thrive across Wellington.

The CBD and Port become critical focus areas, preventing predator ingress into cleared zones. We’re tackling unique challenges: high rise buildings, an operational port and making the Southern Landfill rat free!

We’ll also be doubling our volunteer network, deepening community ownership of this mahi (work).

Phases 4 and 5 push us along the Skyline and through the north to Porirua, presenting entirely new challenges. The work shifts dramatically: large tracts of rural area, much broader geographical scale, more dispersed communities. The predator mix changes too – more possums, more mustelids. These phases take us to the edge of Wellington City.

The five phases of our project.

The five phases of our project.

Five ambitious phases. One limiting factor: funding.

We face a waiting period while DOC finalises the Predator Free 2050 strategy and government funding decisions are made. But we can’t afford to slow down now and lose the gains we have made. You can help by getting involved and letting government know this work matters – that you care about Wellington’s biodiversity future.

For Cities and Conservation Organisations: The Urban Blueprint is available now. We’re actively supporting cities looking to replicate this model and eager to share operational learnings, community engagement strategies, and technical innovations. Let’s accelerate urban conservation together.

For Researchers and Institutions: Wellington is a living laboratory generating real-world data on urban ecology, social transformation, and community-led conservation. Collaboration opportunities span biodiversity monitoring, social science research, and innovation trials.

For Donors and Supporters: We need you more than ever – even with renewed DOC support, and the support of our Councils, Partners and Anchor Donors. This bold mission for Wellington is succeeding, we’re nailing it here and scaling it far – but progress will only be possible with greater investment.

Your support enables us to keep moving, and to:

Every dollar invested delivers measurable returns – ecological, social, and economic. Current ROI stands at $2.49 per dollar invested, and this increases as we scale.

A Predator Free Wellington field worker installing a trap in Mt Victoria. © Tim Sutton

A Predator Free Wellington field worker installing a trap in Mt Victoria. © Tim Sutton

Imagine what’s next: more native species thriving, more neighbourhoods engaged, more cities inspired

HELP US get there

We’re working hard to raise awareness about the benefits of being predator free, as this is crucial for driving the predator free movement. By sharing our experiences – the progress and the challenges – we aim to inspire collective action and help other communities see what’s possible.

As the urban exemplar, Wellington leads by making our learnings visible and accessible, proving that predator free cities can be achievable.

When we set out on this journey as a proof of concept, we knew we were attempting something unprecedented. Now, as our team continues to roll through Phase 2, pushing closer to the CBD and encountering new challenges along the way, it is the broader outcomes embodied in our work to become the world’s first predator free Capital City that we are able to quantify that are truly outstanding. Our Most Significant Change Evaluation and the Cost Benefit Analysis Report demonstrate the true value of this kaupapa to our people and our place.

While we don’t often pause to acknowledge our own staff at Predator Free Wellington it is important to do so. The team are an incredible group, their ability to shrug off adversity and continuously meet the challenges of the unknown is both inspiring and humbling. While the project continues to roll on seemingly unabated it is important we remember that it is the people behind the project that are not just fronting up every single day to get the work done. They are also the ones continuously innovating to refine operational methods, drive efficiencies and work in new ways to deliver results. I hope you enjoyed reading about the trials and tribulations of bringing to bear new tools and approaches to solve problems in a real world setting in real time.

A key feature of our work at Predator Free Wellington is sharing our learning with others – that involves the good, the bad and the ‘jeepers, I wish that hadn’t happened’. Part of who we are is contributing what we have learnt so that others can pick up the ball and deliver on their own aspirations in their places, whatever they may be. Learning is the constant thread of this report; it is not one neatly titled section with associated bullet points. It is inextricably woven throughout and I encourage you to re-read our Impact Report with that theme in mind.

This year we were lucky enough to be accepted to present our work at the IUCN World Conservation Congress in Abu Dhabi. With over 10,000 participants from 189 different countries it was a phenomenal opportunity to showcase what it is we do on the global stage. It was fantastic to learn from other projects about the evolution of urban based conservation underway and share our own success in mobilising a city to deliver something that has never been achieved before together as a collective.

Predator Free Wellington genuinely belongs to everyone and we could not achieve what we have without the support, dedication and leadership of the people of Wellington, so thank you! I would also like to pass on a huge thank you to the hundreds of Predator Free Wellington volunteers for investing your time and energy in the transformation of our city.

Funding remains an enormous challenge, and our team acknowledges the extraordinary group of partners, sponsors and donors who are stepping up to that challenge. Heartfelt thanks to our foundation partners Wellington City Council, Greater Wellington, The NEXT Foundation, Predator Free 2050 Ltd, and Taranaki Whānui ki Te Upoko o Te Ika. They are joined by a growing number of very special sponsors, grant bodies, and private individuals all pitching in to help fill that gap.

Valued partners Wellington Airport, Russell McVeagh and media partner The Post are joined by supporting sponsors Fix & Fogg, Mitre 10 Crofton Downs, Kiio, Athfields Architects and Paremata Auto Services. Our seven wonderful Anchor Donors: Denise Church & Michael Veneer, Tim Clarke & Tessa O’Rorke, Cathy Ferguson & Mike During, Heather & John Hutton, Shirley Vollweiler & Len Cook, Kathryn Jones & David Long and Karen & Kevin Baker lead a donor programme that is open to all through our website. Support from Port Nicholson Rotary, Nikau Foundation and Lottery Environment & Heritage rounds out our support base at present.

Core support from government has significantly reduced for this and other projects in the Predator Free 2050 mission. While we work to address this and value DOC’s support in that, we know that 98% of Wellingtonians want their city to succeed in this game-changing mission. We would love you to join our donor base if you can.

— James Willcocks, Project Director

Help us reach the whole of Wellington City

whether through time, traps or funding – WE NEED YOU in this