2023/24 Impact

MAKING THE IMPOSSIBLE POSSIBLE

Scroll down...

Scroll down...

Kia ora koutou,

With the Miramar mission complete, this year has had one primary focus: optimisation. Now that we know how to do this, we have to go harder and faster, which is exactly what we are doing through Phase 2 as we march towards the CBD and beyond.

As you read through this report, you’ll see how new technology and innovation, combined with hard graft and determination, are driving our mission forward: it is super exciting. This is not just about Wellington anymore – as we’ve developed the methods and continue to push the limits we are actively sharing what we’ve learnt to build capability and inspire others to tackle gnarly environmental issues. Collectively we are taking the ‘Wellington way’ to the nation and to the world.

While the phenomenal bounce back of native species we are seeing provides the ultimate answer to the WHY question, what continues to astound me are the broader impacts of our work. Strong friendships, community connectivity and resilience, equity, health and well-being outcomes are all inextricably intertwined with the collective effort of this scale. We are not just delivering an epic legacy for our city, we are providing direct benefit to every single person living in the project area.

All movements require belief and support from the outset. Delivering something unprecedented demands even greater faith and backing. I extend my heartfelt thanks to our foundation partners: Wellington City Council, Greater Wellington Regional Council, The NEXT Foundation, Predator Free 2050 Ltd, and Taranaki Whānui ki Te Upoko o Te ika. Without your unwavering commitment, we wouldn’t even have a boat, let alone this remarkable journey on which we’ve embarked. Also, a huge thank you to our more recent sponsors, contributors and partners. Your generosity is adding critical fuel to the engine: momentum is crucial and you’re ensuring we can maintain it!

The achievements highlighted in this report are remarkable and belong not just to the team at Predator Free Wellington but to the thousands of Wellingtonians who are working tirelessly to create a future unique to our capital city. While we face challenges like any urban centre, we must remember that together we have built something extraordinary – something that continues to elevate our fine city on the global stage.

This is your report – thank you for everything you give to this mission. Enjoy the read!

— James Willcocks, Project Director

Ehara taku toa i te toa takitahi engari he toa takitini

Our strength does not come from ourselves alone, our strength derives from the many

In November 2023, we announced we had successfully eliminated ship rats, Norway rats, stoats and weasels from the Miramar Peninsula.

Widespread and equitable participation across the project. This means the ecological and wellbeing benefits, such as rat-free homes or increased wildlife, and potential benefits of participating, such as improvements to people’s psychological and social wellbeing, are not limited to particular sectors of society.

The outcomes of our work on the Miramar Peninsula are a tribute to an epic collective effort.

The project relied on the support of 20,000 locals, and involved almost every business, school and kindergarten, hundreds of volunteers, Predator Free Miramar, technical experts, and our foundation partners Greater Wellington Regional Council, Wellington City Council, Predator Free 2050 Ltd, NEXT Foundation and Taranaki Whānui ki Te Upoko o Te Ika (Port Nicholson Settlement Trust).

Predator Free Wellington’s Phase 1 on Miramar Peninsula was completed in November 2023, and Phase 2 is now well underway. Enjoy this video to gain insights into our project and the systems being used to eliminate target species across the 30,000 hectares in and around Wellington City.

Our work on the Miramar Peninsula marks just the start of a much larger mission. We’ve developed a successful recipe for removing rats and mustelids from an urban environment, and to celebrate this milestone, we have created an easy-to-use, step-by-step blueprint so others can replicate our success.

Importantly, the learning doesn’t stop here. This blueprint reflects what we have learned to date. We know how to effectively remove these target animals, but our next step is to discover how we can do this faster and more economically. We are focused on optimising our work, and there will be future versions of this blueprint that include our ongoing discoveries and innovations.

By sharing what we’ve learnt and supporting one another, we can collectively work towards Aotearoa’s ambitious goal of becoming predator-free by 2050.

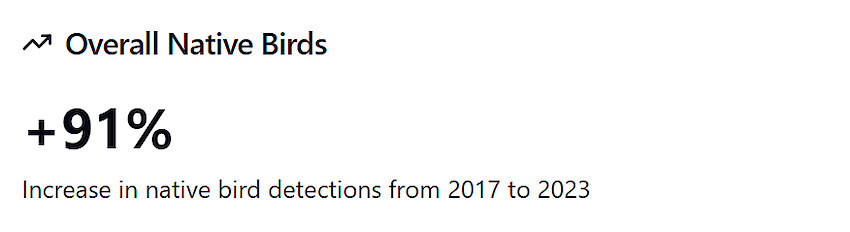

We’ve been tracking birds on the Miramar Peninsula since 2017. This is what we’ve found and why it matters.

Native bird numbers have almost doubled! These results show that when urban predator elimination projects work, they really work.

These results show that when urban predator elimination projects work, they really work.

When you remove introduced predators (rats, stoats and weasels) from an urban environment, it leads to outcomes for biodiversity that are not just a little bit better, but many times greater.

Looking at our indicators

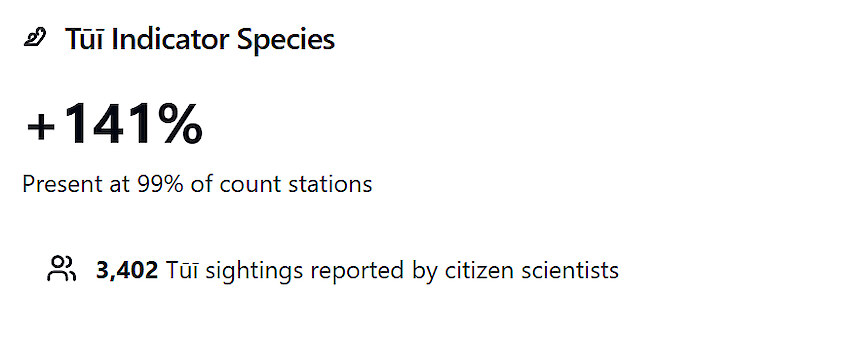

Indicator species are often the first species to be affected by any change in their ecosystem. A positive change may increase the population, while a negative change may cause a decrease.

We chose tūī as the indicator species for our project, as they are not only a distinctive and conspicuous bird species that many local residents appreciate and recognise, but they have also historically responded well to predator control in Wellington City.

Tūī are present in all the major habitat types on the peninsula but appear to be more common in native forest habitat. We saw this particularly around Mt Crawford and in suburbs with greater tree cover and more mature gardens such as in Seatoun and along the eastern bays.

Tūī are present in all the major habitat types on the peninsula but appear to be more common in native forest habitat. We saw this particularly around Mt Crawford and in suburbs with greater tree cover and more mature gardens such as in Seatoun and along the eastern bays.

Recolonising birds

Citizen scientists recorded kākā and kākāriki on the Miramar Peninsula on eight and 20 occasions respectively. This is an early sign that these two species are in the process of recolonising forested habitats on the peninsula.

Both species were successfully re-introduced to Zealandia and have been steadily expanding their distribution throughout Wellington City in recent years. Kākāriki also live on Matiu / Somes Island. Local resident Lance Lones spotted this kārearea by Oruaiti Reserve.

Local resident Lance Lones spotted this kārearea by Oruaiti Reserve.

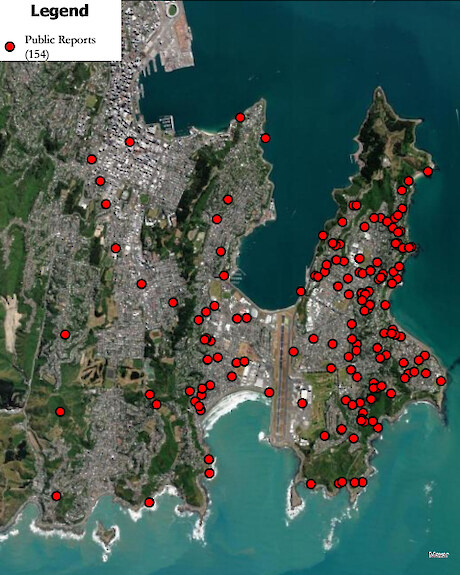

Residents have spotted kārearea (NZ native falcon) all over Miramar Peninsula, from native forests to urban areas, even flying over Wellington Airport. The clusters of sightings near Shelly and Worser Bays likely show where several breeding pairs hang out, proving just how adaptable and present these falcons are in the area.

A network of 84 five-minute bird count stations has been established on Miramar Peninsula to monitor the response of local bird populations to the elimination of rats and mustelids from the peninsula.

A single bird count has been carried out at each count station in November or December each year between 2017 and 2023.

“When I heard they wanted to eradicate the whole peninsula I was happy to give it a go, but I never imagined we would see this amount of change. I never imagined I would have a pair of kārearea nesting 500 metres from my house.”

Marcus, Seatoun resident and Predator Free Miramar volunteer.

Following the successful elimination of rats and mustelids from Miramar Peninsula, the project has been entrusted to the local community for ongoing biosecurity management. Returning control to the community does not equate to abandonment; rather, it signifies a high-trust collaborative effort.

This community partnership is not only working, but is achieving results at a fraction of the cost.

The Miramar Peninsula biosecurity response depends on a vigilant community of 20,000 residents as our eyes and ears, reporting any sightings via our dedicated 0800 NO RATS number. Additionally, a skilled volunteer team, intimately familiar with the local environment, plays a crucial role in maintaining the area’s biosecurity.

This is supported by our existing detection camera and trap network that can be reactivated as needed and specialist detector dog teams who can respond to incursions almost immediately. Through our Predator Free 2050 networks and foundation partners we also have on-call experts available to offer support, tools and advice.

With this team in place, we can successfully manage incursions in our biosecurity zones, and protect our hard won gains in an efficient and cost-effective way. For the stoat incursion on the Miramar Peninsula, we were able to successfully manage the incursion in not only a similar timeframe to previous predator free island responses, but also at just 3% of the cost*.

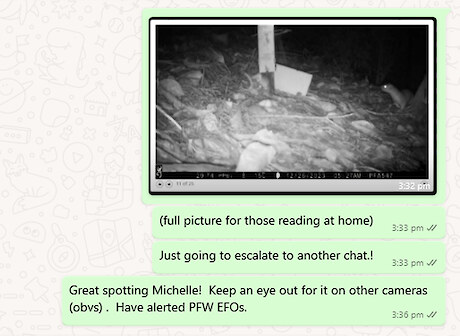

In December 2023, a stoat was sighted on the Miramar Peninsula. This was part of our Phase 1 project, where we had successfully eliminated stoats, weasels and rats.

In December 2023, a stoat was sighted on the Miramar Peninsula. This was part of our Phase 1 project, where we had successfully eliminated stoats, weasels and rats.

Identification Whatsapp volunteer chat messages

Whatsapp volunteer chat messages

On 12 December 2023, volunteer Michelle Wilhelm identified a stoat on camera.

Over the following seven months, Predator Free Miramar volunteers checked images weekly, seeing the stoat nine times on camera.

Expert analysis determined we were chasing a lone male stoat which changed our risk profile; a pregnant female would need a different response!

Making decisions

With full support from the Miramar community and our team making great progress in Phase 2, we had some decisions to make. We are finely balanced between moving forward with the project and ensuring we are detecting and removing invaders from areas we have cleared.

Working with our technical partners (ZIP) we made the call to trust our detection cameras and our highly skilled Predator Free Miramar volunteers.

And it worked!

If you were a stoat, where would you go?

Stoats can travel over 70 km when they are finding their own territories. They can also easily swim 3 km between islands. So we were working with a big territory.

Our cameras showed this stoat appeared to have a base in the Northern Bush, but it was also spotted on camera at Oruaiti, Beacon Hill, Maupuia and Lyall Bay. It may have even travelled as far as the city.

We engaged Brad Windust and his stoat scat detector dog Wero to scout the peninsula. They searched for signs of mustelids, food caches, dens, play sites and scat. After scouting the peninsula for a week Wero indicated one site in northern Miramar as a play site and one potential place of interest in Lyall Bay.

Brad’s gut feeling was this stoat was only a visitor to Miramar, explaining he would have found more scat if it was living there.

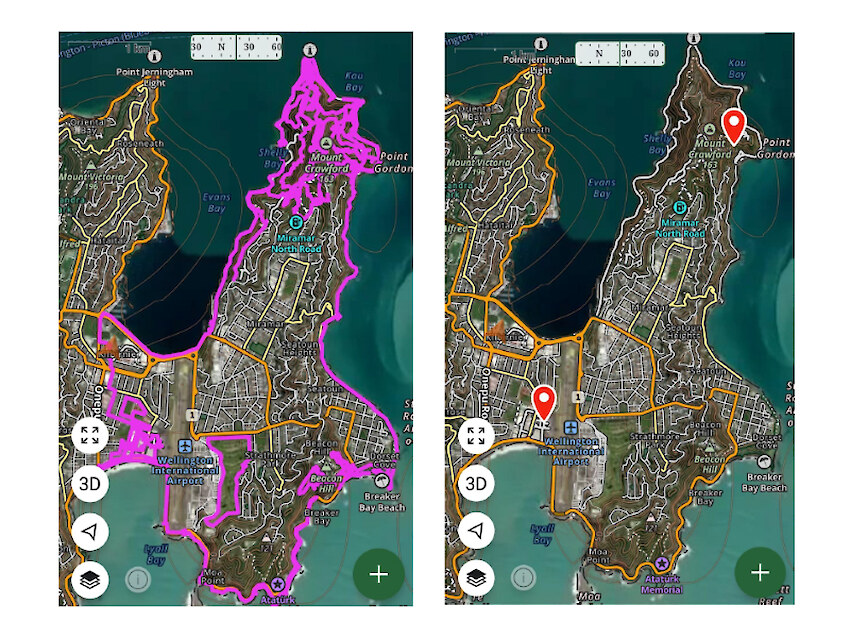

The pink lines show Brad and Wero’s track logs. The red markers indicate stoat scat and play site.

The pink lines show Brad and Wero’s track logs. The red markers indicate stoat scat and play site.

Bringing in the experts

To support our response, we enlisted John Bissell from Backblocks Environmental Management to share his expertise. This empowered and equipped the Predator Free Miramar volunteer crew to lead the response.

John uses a mix of science, hunting and gut instinct. He specialises in targeting one animal in a large landscape.

John advised the crew: “The stoat is not just going to blindly walk into a trap just because it happens to be there… You have to think like a stoat.”

And that called for a change in strategy and mindset.

Scorching Bay: Stoat scat site and play site found by Brad and Wero (NB. traps were added after the sighting)

Scorching Bay: Stoat scat site and play site found by Brad and Wero (NB. traps were added after the sighting)

Leaning in to the hunt

The skills of the Predator Free Miramar volunteers extend so far beyond basic trapping. They call themselves the ‘flying squad’ and are creative problem solvers who volunteer most Sundays.

Every weekend since the first stoat sighting in December, volunteers were rebaiting and moving traps near to where the stoat was seen. But there was an underlying sense of frustration after months without success.

Following John’s visit, the volunteer trappers had renewed confidence and a deeper awareness of what was needed to catch this stoat. They knew it was a fool’s errand to manage hundreds of traps; instead they needed to do a handful of traps really well. They chose premium sites that were freshly baited and beautifully presented.

Years of trapping rats meant they knew the landscape intimately. Features like ridges, streams and roads guided their thinking. Bush edges and fence lines hid the stoat from predators like kārearea (NZ falcons) and kahu (hawks): these were good places for traps.

The trappers used heaps of fresh red meat (beef, mutton and venison) and stoat bedding. The tennis ball-sized bedding was a visual lure, with the idea that if the stoat wasn’t hungry it might be curious about finding a mate or fighting off another stoat.

A successful catch

After 207 days and 755 hours of volunteer time, the Predator Free Miramar volunteers caught the stoat in trap number BT302 (north of Massey Memorial). It was lured with aged venison and male stoat bedding.

The trap was cleared by Gerard Hutching and Mike Arnerich, two of Predator Free Miramar’s regular weekend trappers. The trap itself had been moved several metres into a better position six weeks prior by Mike and John Herrick and the new site (and lure) proved to be a winner.

In the end, Dan Henry (Predator Free Miramar Lead) believes it was a series of small decisions that made the difference. Story in The Post celebrating the volunteers catching the stoat.

Story in The Post celebrating the volunteers catching the stoat.

“It wasn’t a super stoat that’s too smart. It was catchable, with effort, persistence and creativity,” said Dan.

The volunteers were given the freedom to lead the response and that was part of the appeal, along with the mateship and a sense of community.

This won’t be last stoat we encounter but we are pleased to have this one dealt with, and it provided a perfect testing ground for our community biosecurity response. We got the result and are defining a new model for biosecurity response at a fraction of the cost.

What we now know

The invading stoat was sent for genetic testing at Manaaki Whenua, revealing that the animal was a young male, born in September 2023. Likely dispersing in search of territory.

Genetic sequencing indicates that this stoat is most closely related to one previously caught near Makara Beach, followed by another from Tongue Point. These relatives are not from the same litter or parents, meaning they are more distantly related, like cousins or grandparents.

These findings highlight a significant geographic spread, as stoats are known for their ability to traverse considerable distances. Importantly, now that we know the likely origin, we can confirm that the stoat did not swim across the harbour to reach the peninsula; rather, it entered by land. Understanding these details helps us adapt and improve our biosecurity response systems.

*Cost savings were compared to a recent effort to remove a stoat from Chalky Island in Fiordland, which cost almost $500,000 NZD.

We are reducing costs of managing biosecurity and predator incursions.

Predator Free Miramar volunteers invested 755 hours of their time to the stoat incursion effort.

The Miramar community are essential for spotting rat invaders; they are our constant eyes and ears on the ground. Reporting possible rat activity is quick and easy, and for residents of Miramar it’s a natural expression of kaitiakitanga (guardianship).

112 Miramar residents reported potential rat activity between January - September 2024.Between January and September 2024, residents reported 112 cases of potential rat activity. While the vast majority of these turned out not to be rats, we were grateful for the reports.

112 Miramar residents reported potential rat activity between January - September 2024.Between January and September 2024, residents reported 112 cases of potential rat activity. While the vast majority of these turned out not to be rats, we were grateful for the reports.

For our team, finding a rat in a cleared area is no reason to panic. We expect some individuals to reinvade and we use the same approach that removed rats in the first place. This is the system working and we are massively thankful to the community for helping us to keep Miramar Peninsula rat and mustelid free.

Rapid rat response

We take all rat sightings seriously, and aim to respond to every report within 24 hours.

There is no one-size-fits-all response to returning rats, but we generally get rat detector dog Rapu and handler Sally on the case.

If Sally and Rapu verify there is a live rat present, we then send in our Capture team.

The Capture team are our incursion specialists and will create a response area with a 150 metre buffer from the detection. Managing the response involves analysing camera footage, re-engaging with residents, servicing traps and bait stations and placing out additional detection cameras and chew cards over a wider area.

Response areas are treated much like rat hotspots, where the data is critically assessed after every visit and the servicing frequency, area and regime adjusted accordingly.

We’re always watching

Can we still call these areas ‘predator free’? Absolutely. We know rats or stoats can slip back in and we have a proven system to detect and remove them. No one is looking harder than us. Wellingtonians also fully support having a predator free city and their reports are essential. We are confident there are no rats in biosecurity areas and when we occasionally find one has snuck in, the Capture team swoops in to take care of it.

Read more about our Capture Team here.

Everyone realises we need to be vigilant, keep monitoring and report sightings so we can mobilise to catch the rat or stoat.

Sue, Predator Free Miramar Volunteer

Residents know to call 0800 NO RATS if they see any rat activity.

Residents know to call 0800 NO RATS if they see any rat activity.

Genetic sequencing data of the last remaining rats on the Miramar Peninsula has provided insights into the local rat population, and a snapshot into the effectiveness of our biosecurity efforts.

This genomic study, the first of its kind in a New Zealand elimination project, aimed to uncover the genetic relationships among the last remaining rats on the Miramar Peninsula. By mapping their genes, we are able to distinguish between local rat survivors and new invaders, making our biosecurity efforts more targeted and efficient.

What we did

Our container of rat tail snips for DNA testingThis was a genomic study, which means it explored the genes and DNA of a plant or animal. From mid-2022 to late 2023, we caught the last ship rats on the peninsula. We collected a short piece of each rat’s tail and sent these to Andrew Veale at Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research. The 74 samples gave 30,000 genetic markers, which helped Andrew and the team create a detailed map of the population.

Our container of rat tail snips for DNA testingThis was a genomic study, which means it explored the genes and DNA of a plant or animal. From mid-2022 to late 2023, we caught the last ship rats on the peninsula. We collected a short piece of each rat’s tail and sent these to Andrew Veale at Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research. The 74 samples gave 30,000 genetic markers, which helped Andrew and the team create a detailed map of the population.

What we found

Their work showed two distinct groups – rats on Miramar Peninsula were genetically different from those in Rongotai and Lyall Bay. We have a buffer system of traps, cameras and bait to prevent rats returning to the Peninsula. Looking at a genetic level showed that our system worked. The final ship rats we caught during our elimination were Miramar rats: they hadn’t snuck in from other areas.

What it means for our project

We now know what a ‘Miramar rat’ looks like, genetically. When we catch rats on the peninsula in the future, we can compare its genes to our existing data to learn if it was an invader or had avoided us all along. In the past we’d have to guess where rats came from; now we know. As we move across the city, we’ll build a genetic map of rats from different areas.

This study also confirmed what we know about rat behaviour. Normally, closely-related rats stay close to each other. When rat populations are incredibly low, individuals will travel far searching for mates. This means when we find a lone rat, we need a wide buffer to catch other individuals that could be up to 2km away.

We’ll use this data to help refine how we work. This will be especially helpful as we move into later phases of the project, which cover large and challenging areas. The more we understand rat populations, the quicker, smarter, and more cost-effective our path to a predator-free city will become.

In our Phase 2 project, the focus is on optimisation. We have proven we can successfully eliminate rats and mustelids in an urban setting, our next challenge is to accelerate the process and reduce costs.

This is the necessary step to achieve the ambitious Predator Free 2050 New Zealand goal.

What’s involved? This second phase involves 14 suburbs from Kilbirnie around to Ōwhiro Bay and up through to the CBD. It is home to approximately 60,000 residents, and includes Wellington Zoo, Government House, Massey University and Wellington Regional Hospital.

The full Phase 2 rollout will see the installation of 2,596 traps, 8,488 bait stations and more than 500 detection trail cameras.

How many rats are out there? It’s a tough question to answer as it’s not just about counting rat catches: we also consider bait station interactions, chew card monitoring and data from our detector dog team. Based on our findings from our work in Hataitai, we estimate there’s at least one rat for every two people.

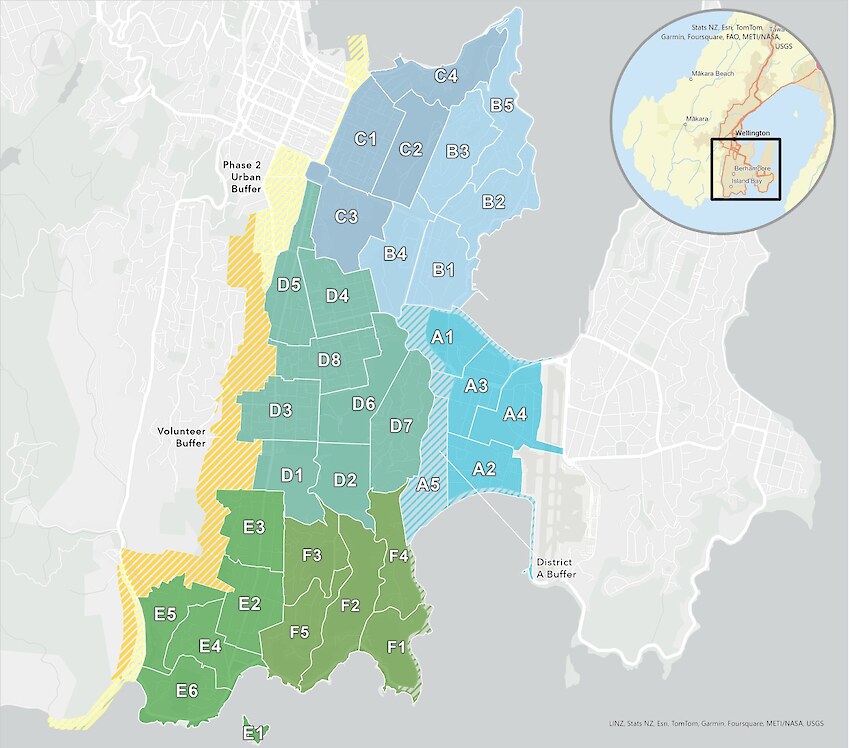

How fast are we moving? In a strategic shift from our approach on the Miramar Peninsula, Phase 2 has been divided into 32 distinct zones. Splitting the area helps us target our approach more effectively based on the habitat and land use. Map showing the 1400-hectare Phase 2 project area, divided into Districts (A - F) and Zones (numbered).

Map showing the 1400-hectare Phase 2 project area, divided into Districts (A - F) and Zones (numbered).

We use a ‘rolling front’ approach: beginning our operations in one zone (usually the most easily defendable from reinvasion) and progressively moving across the landscape, eliminating rats and mustelids zone by zone until each district is completed. This creates a moving front line, with some zones actively being worked on and others already cleared and protected from reinvasion. We can open new zones as we finish the previous ones and free up staff. Think of it like puzzle pieces fitting together; over time, the cleared area will grow until the entire phase is complete.

This approach has been successful; it allows us to work intensively in a small area to reach elimination without biting off more than we can manage at one time. Spreading ourselves too thin over too large an area was one of the reasons ship rats weren’t eradicated from the Miramar Peninsula on the first attempt. While we can suppress rats on a large scale, completely removing them is much harder. The size of each zone will depend on factors like team size, resources, geography, and urban development.

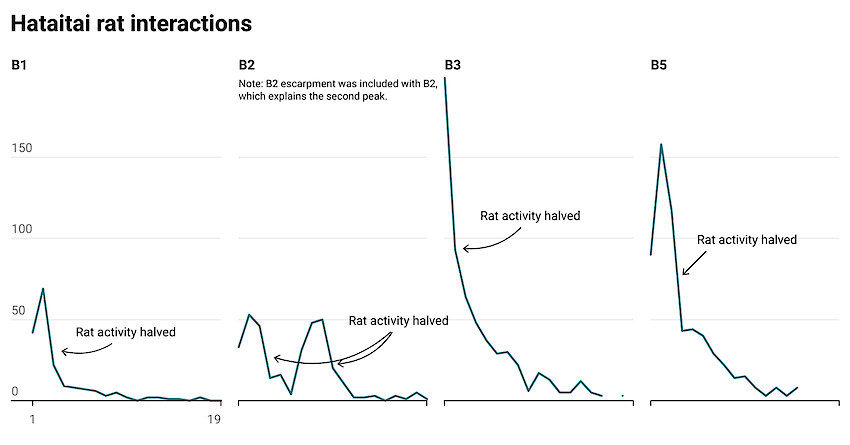

On average we can halve the rat population after two services (four weeks), and you can see from the examples below how quickly we are getting the rat numbers to almost zero.

These charts illustrate the reduction of rat populations in our Hataitai zones over time, based on fortnightly services by our field team.

These charts illustrate the reduction of rat populations in our Hataitai zones over time, based on fortnightly services by our field team.

Blake from our field team installing an H2-ZeroThe introduction of ZIP’s H2-Zero, a device that slowly releases liquid bait for rats, is set to revolutionise pest control efforts.

Blake from our field team installing an H2-ZeroThe introduction of ZIP’s H2-Zero, a device that slowly releases liquid bait for rats, is set to revolutionise pest control efforts.

We began a trial of new bait stations and dispensers in Mt Victoria in July 2024. This trial involves a large network of secure Lola tunnels that contain the newly developed H2-Zero dispensers, both produced by ZIP.

The H2-Zero dispenser uses a hydrogen-producing coin cell battery that allows the gas to expand and pushes down on a syringe to gradually release 125 ml of lure over a three-month period. The lure contains rat toxin. This system can be left for several months, allowing the removal of many rats with minimal effort.

One of the big challenges in keeping a predator-free environment is the costs of regularly monitoring and maintaining rat traps and bait stations. Currently, these need to be checked on a fortnightly basis, which takes considerable time and resources.

However, with the H2-Zero technology, we can check the devices less often. By extending the interval between checks to a monthly schedule, the workload is effectively halved. By reducing labour, this drives down our overall costs and allows our field teams to work in other parts of our Phase 2 project area.

Around 30 trail cameras are being used to monitor the rat population as it declines, see how effective the new method is, and detect any animals left behind. These cameras also help observe rat behaviour and how they interact with the stations.

If the system proves successful, we plan to use it across more of our project area, helping us clear larger areas more cheaply and quickly.

Predator Free Wellington volunteers* dedicate more than 55,000 hours a year to achieve our predator free mission.

This huge contribution is equivalent to having an entirely new Predator Free Wellington field team, valued at approximately $2 million a year in support.

The monetary contribution of volunteers is a crucial aspect of their value, but it only scratches the surface of their overall impact. When we complete our project by 2030, it means we’ll have hundreds more trained volunteers across the city, and thousands of households, watching for signs of rats.

Expanding across the city

Phase 2 of our project extends from the CBD to Island Bay, moving east from Rongotai and south from Oriental Bay, Roseneath, and Hataitai. The western edge of Phase 2 is protected by our buffer: an area filled with traps and bait stations that hard-working volunteers maintain. The buffer lowers the chance of rats slipping in from the west and means we can focus on our suburb-by-suburb approach.

John Cleveland leads one of our buffer teams. The Mātairangi Tonga group of Community Rangers monitor 40 hectares of southern Mt Victoria bush, covering the Hataitai velodrome, the badminton hall and the SPCA building. Between April and early October 2024 they checked bait stations 1,480 times, caught 14 rats and recognised 193 instances of bait take! This important work protects mostly rat-free Hataitai from the rest of the Mt Victoria town belt where the Predator Free Wellington team is working.

Learn more about our community heroes here.

Providing training and support

We train the buffer volunteers and trust them to effectively manage their areas. Lee Rowland, the lead for Prince of Wales Park, explains that her team ‘check and refill bait stations, make records, recognise signs of rat activity and understand rat habitat. They are all shrewd observers, and independently decide whether a bait station is in the best spot or should be moved.’

The skilled buffer volunteers share their data with us and deliver rats they catch to local lockboxes. We include these rats in our genomic studies of rat populations: our volunteers are held to the same standard and bring rats out to base as the rest of our team does. This information helps us develop our Phase 2 work. The lockboxes also house tools and equipment the volunteers need.

Community partnerships in action

Our work with volunteers has also expanded to include partnerships with notable parts of Phase 2. This includes working with Te Papa’s Tory St facility, Massey University, Wellington College, Pukeahu National War Memorial Park and Government House. Together these areas cover more than 30 hectares. For each location, we trained staff, students or contractors.

Governor General Dame Cindy Kiro supports the project, saying ‘Wellington has already demonstrated it is the greenest city in the world in the way it’s reserved that space through a green corridor. It is a wonderful vision for New Zealand being predator free.’  Governor General’s pest control team are eliminating rats at Government House

Governor General’s pest control team are eliminating rats at Government House

We appreciate the support of the Nikau Foundation which funds our training of these groups.

Essential support for our project

These partnerships are vital because they allow our field team to keep moving forward. We are confident that skilled volunteers are monitoring the buffer. Add to this the thousands of Wellingtonians with backyard traps and many more checking traps in reserves across the city. This huge collective effort suppresses rat numbers. It also lets us focus on one zone at a time as we methodically follow our ‘remove and protect’ model.

*Predator Free Wellington volunteers include Predator Free Miramar, Phase 2 buffer volunteers and the 60 backyard trapping groups working across Wellington.

While we’re still only halfway through Phase 2, we are already gearing up for Phase 3, which will be our biggest yet. This phase will extend our efforts further into the city, following a line from the port to the western fence of Zealandia and out to the sea. We’re particularly excited about the possibility of having the world’s first rat-free rubbish tip!

We’re also seeing growing interest from communities north of Wellington, including the Kapiti Coast and Porirua, all eager to leverage our work and pursue their own predator-free goals. This would be a natural extension of the predator free movement across the city and our role here is to share what we know and provide guidance and training to help these communities succeed.

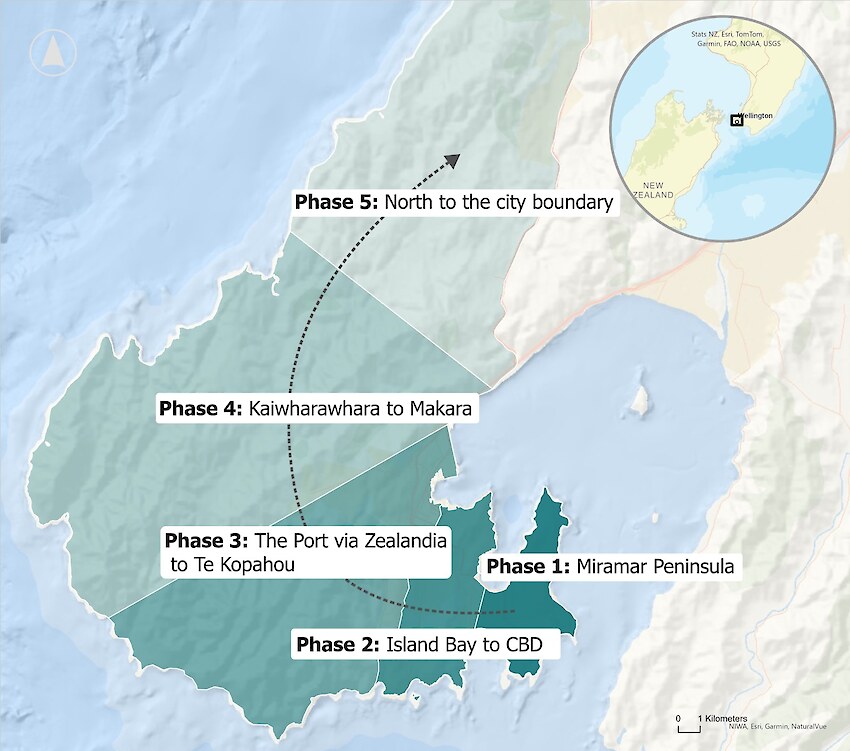

Map showing the five project phases, beginning with Miramar Peninsula and progressing west.

Map showing the five project phases, beginning with Miramar Peninsula and progressing west.

Understanding wider outcomes

Our Phase 1 elimination was our test bed, and over five years we trialled systems and processes, studied the behaviour and makeup of our target species, engaged every second household (10,000 residents) in our mission, and landed on the best method for urban elimination of rats and mustelids. Miramar Peninsula is now predator-free and, in partnership with the community, we are keeping it that way.

But what we actually deliver is so much more than the ecological and conservation outcomes of immediate biodiversity bounce back.

Our project has social, health and well-being outcomes. For some impacted by our project it’s not the conservation outcomes that are the priority, it’s improving food security, or it’s stopping rats chewing through pipes or cables and causing catastrophic damage. Levels of depression, anxiety and stress are lower in people who spend more time in nature and creating that environment together leads to greater feelings of social cohesion (Whitburn & Shanahan, 2022). The public health benefits of removing rats and the diseases they spread to humans will be significant (McIntyre, 2022). The economic impact of all of these game-changing outcomes is still to be fully understood, let alone the impact on our tourism and visitor story.

So we’re not only changing biodiversity forever, we are delivering health, wellbeing, social and economic outcomes that will create impacts for generations.

Our biggest challenge now is funding

Government funding to this national mission, via Predator Free 2050 Ltd, has significantly decreased – the number of projects supported by government has dropped from 18 to just five, of which Predator Free Wellington is one. But our funding level from Predator Free 2050 Ltd has also dropped, from $2 million per year to $500,000.

Our proven system for our mission costs $4 million a year to deploy, so that drop from government results in a $1.5 million a year gap – from 2025/26 until we complete the project in 2030.

Predator Free 2050 Limited, Greater Wellington Regional Council, Wellington City Council and the NEXT Foundation are now being joined by sponsors, grant bodies, and private individuals in a concerted effort to fill that gap.

We have welcomed new sponsors Wellington Airport, Russell McVeagh and media partner The Post. We have launched a new Anchor Donor programme with six generous Wellington donors on board so far. We also have two public donation campaigns on our website: one to support the mission generally and the other to help us hold the line against reinvasion when we have cleared zones across the operational area. We have had support from the Nikau Foundation this year, and just as we go to publish this, a grant from Lottery Environment & Heritage. We continue to have Fix & Fogg and Mitre 10 Crofton Downs support in kind, and this year they were joined by Kiio, the events production professionals.

With 98% of Wellingtonians supporting our mission (Wellington City Council Residents Survey, 2023), we are doing what we can to bridge the funding gap, at the same time as advocating strongly for the importance of this project to central government, ensuring it remains a priority for both Wellington and New Zealand as a whole.

Another focus for us is telling the personal stories around the impacts.

Most significant change

While addressing ecological challenges is crucial – it’s the core of our mission – we recognise that our project offers benefits that extend far beyond environmental.

Predator Free Wellington is not just a conservation project; it’s a community-driven movement that strengthens connections and enhances well-being. As residents participate in trapping and other related activities, they not only help protect our unique wildlife but also build friendships and a shared sense of purpose.

To gain deeper insights into the broader impacts of our project, we are undertaking qualitative research using a method called Most Significant Change.

This approach allows us to better understand how involvement in our project impacts the community, and helps us understand what changes have been most significant from an individual perspective.

Here are some key themes of impact:

Community buy-in and social cohesion:

Changes in biodiversity

Changes to the quality of people’s lives

Innovation change

We’re working hard to raise awareness about the benefits of being predator free, as this is crucial for driving the predator free movement. By sharing our stories with local and international media, we aim to spread the word even further and inspire collective action. In addition to raising awareness, we’re also sharing our learnings along the way and collaborating with other predator free groups and communities across the country.

Message from the Chair

“Have you caught that stoat yet?” became a Wellington catch cry this year, right up there with “thank you driver”. Such was the interest, both here and even internationally, in a lone stoat invader – since deceased – in a now predator free Miramar peninsula. The success of this urban first has established Predator Free Wellington as an exemplar for the Aotearoa-wide Predator Free 2050 vision.

With a government more concerned about the bottom line than biodiversity, our biggest challenge is absorbing sharp funding cuts. We are facing a $1.5 million hole, a significant chunk of our budget, and are appealing for more corporate, philanthropic and individual support. That is a tough challenge but it will not derail us. The Greater Wellington Regional Council and Wellington City Council remain staunch supporters. And we are learning to be smarter and more efficient as we move from Phase 2 from Island Bay to the CBD to the suburbs further west.

While sufficient funding is vital, our greatest asset remains our dedicated, hard working staff; committed board members and, not least, the hundreds and hundreds of enthusiastic volunteers who have embraced the predator free concept and revelled in a return of the dawn chorus.

In a cool little Capital that is suffering chilly winds, Predator Free Wellington, in concert with Zealandia and Capital Kiwi, is a beacon of good news. In the rest of the world wildlife is under assault. Wellington lays claim to being the only capital city on the planet where biodiversity is increasing.

Several years ago when walking the 3000-km Te Araroa Trail from Cape Reinga to Bluff with my wife Sue and Dame Kerry Prendergast, we were struck by the silent forests. The predators had won. But not in Wellington. Bellbirds/korimako greeted us with their melodious song on the city’s doorstep and kākā cackled in the town belt. Their numbers, along with tūī in particular and other species, have increased again, as this report details. Attractive geckos and skinks are also enjoying the absence of introduced killers.

Today’s youngsters take the increasing abundance of native birdlife for granted, assuming that was always the case. For a long time the birdsong was stilled but now it is back. That sure is something to celebrate.

- Tim Pankhurst, Chair, Predator Free Wellington Ltd