2018/19 Impact

How do we create the world’s first predator free capital city?

Scroll down...

Scroll down...

Letter from James

As you read through this report, know that you are part of the Predator Free Wellington team.

Predator Free Wellington is about everyday people choosing to define the type of city we live in. It’s about taking action, starting in our own backyards. These choices and actions have a ripple effect, connecting thousands of Wellingtonians to the goal of creating the world’s first predator free capital city.

Our project is about system change, demonstrating that in the face of widespread global environmental degradation a dedicated collective of people can change the tide.

Our stories are changing, Wellington is changing, the way we view ourselves as Wellingtonians and how we connect with each other and nature is changing.

To put this into context, not that long ago for me to be able to see a kākā in the wild would have involved a tramp deep into Pureora Forest Park with maybe the chance to see one or two from afar. Now our kids get to see them most days creating a ruckus in the city’s suburbs and green spaces. That is an incredible thing indeed.

It’s been a huge year preparing for our first phase of eradication on the Miramar Peninsula. We have set ourselves up as an independent charitable entity and appointed a board of fantastic directors. It has taken a huge amount of planning and testing to get us to the point of operational readiness. We have been blown away by the support from the community, two thirds of Wellingtonians are either involved in predator free work or keen to be involved.

On the Miramar Peninsula, 99% of residents were willing to participate in our project, which enabled us to obtain the thousands of individual permissions we needed to undertake the eradication. Our field team workers felt like heroes going about their work on the peninsula and being so well received and supported by the Miramar community - the shared energy and enthusiasm is epic!

We’re learning lots. An urban eradication project of this size and scale is a world first, so adapting to new ways of learning and working is key.

We are working with the best people and must give a shout out to Predator Free Miramar, Te Motu Kairangi and Places for Penguins for their amazing work on the peninsula, Capital Kiwi for their awesome mahi, working to bring kiwi back to Wellington, as well as the thousands of backyard and reserve trappers throughout the city. We have fantastic foundation partners in Wellington City Council, NEXT Foundation, Greater Wellington Regional Council, Predator Free 2050 Ltd and Taranaki Whānui o te Upoko. We are also fortunate to work alongside ZEALANDIA to deliver the Predator Free Wellington schools programme across the Miramar Peninsula.

The Miramar Peninsula is the first step for us before we move out across the broader city landscape. We are finishing a job, certainly not starting from scratch. There are thousands and thousands of Wellingtonians who have been working hard to achieve this for a long time and I would like to thank each and every one of you. At the end of the day, this is about creating a city where our communities and unique native species can thrive. If we get this right and collectively we keep moving together then we have a real chance at gifting an environment to the next generation that isn’t half trashed. It is an amazing thing to be part of.

— James Willcocks, Project Director

Wellington artist Dside designed this artwork for student trapping group Traplordz.

of Wellingtonians

support a predator free Wellington. This is significantly more than the 84% when we last surveyed in 2017.

Wellingtonians are backing up their support with action. An impressive two thirds of Wellingtonians are actively involved in controlling predators in their backyards or in reserves, or have done some predator control in the past.

* Wellington City Council surveyed thousands of Wellingtonians in March 2019 to help us better understand who is involved in predator free work, how they are involved and what resident’s concerns were about the project.

Wellington is rewilding in front of our eyes, penguins are crossing the road for sushi, kārearea stand guard outside our high rise office windows, kākā are keeping the politicians in line at Parliament and we are falling asleep to the beautiful sound of ruru at night.

We also have tui everywhere and as the most common native bird, some residents are concerned about tui noise waking them up in the morning.

This is the new normal for Wellington. The intensive predator control work across Wellington is making a difference, our birdlife is increasing and visitors are blown away as they hear and see more native birds than they have ever seen – let alone in the middle of a large city.

Increase in kākāriki.

The likelihood of encountering kākāriki has increased more than 10 times since 2011. Red-crowned kākāriki are going beyond Zealandia, spotted in Wright’s Hill reserve, Otari-Wilton Bush, Khandallah Park, Huntleigh Park and also the Wellington Botanic Gardens.

Increase in kererū since 2011.

Kererū sightings were the highest in reserves containing original native forest habitat, such as Otari-Wilton Bush and Khandallah Park, but they are also frequently seen in adjacent suburban areas.

Increase in tui, meaning we are now twice as likely to see a tui.

Tui are now common and widespread in Wellington. There was only a small resident population in the mid 1990s.

The annual 5 minute minute bird count is commissioned by Wellington City Council and is undertaken by Greater Wellington Regional Council and Wildlife Management International.

The intensive monitoring over the summer revealed two new native species turning up on Miramar Peninsula that were not previously recorded - two species of shag and a white-fronted tern.

“5.38am, woke to the call of a ruru for the first time in my 10 years on Pretoria Road above Karaka Bay – wonderful!”

Paul Mersi

In a year where monster rats and mega mast seasons were making the news, Wellingtonians stepped up and increased their trapping efforts.

We now have community trapping groups in almost every Wellington suburb, with over 7,000 traps deployed.

Eight new suburban trapping groups came on board this year, including Broadmeadows, Churton Park, Horokiwi, Rongotai, Thorndon, Ohariu, Makara and Makara Beach.

This incredible effort is making an impact, volunteer trappers have caught almost 70,000 pests, and importantly neighbours are commenting on birds and geckos returning to their backyards.

“People are sharing pictures of karearea and ruru in their gardens, and requests for our backyard traps have gone through the roof as people scramble to get involved.”

Dan Henry, Predator Free Miramar community lead

suburbs, covering 8,000 hectares

traps deployed

pests caught

Trapping groups are active across 49 Wellington suburbs.

There’s a reason why an urban eradication of this scale and complexity has never been done before – it’s too hard. Getting to zero predators is impossible according to some critics.

Fortunately, the critics are few and far between, and our team and our supporters believe not only that the goal is achievable, but that Miramar Peninsula can be completely eradicated of rats and mustelids by as soon as Christmas 2019.

Miramar Peninsula is the first stage of our city-wide project. It’s an area of rocky coastline, steep cliffs and sandy beaches. There’s also a large urban area with a mix of residential housing, film studios, cafes, light industry and schools.

This is a place where 20,000 people live, work and play every day - not some offshore island or remote bush block.

So where do you even start with a project like this?

Given that nothing like this has ever been attempted before, we firstly need to test our methodology (tools and techniques). To do this we commissioned two independent peer reviews to test our thinking and planning. From there we wanted to further explore our risk factors so we commissioned a detailed risk analysis to test the things that were keeping us up at night.

We had to test the assumption that rats were using stormwater networks as super highways on the coast.

The Greater Wellington Regional Council monitoring team was on hand to help us investigate. We monitored over 25 separate stormwater outlets around Miramar Peninsula with peanut butter laden chew cards over seven nights. After a week, the tags were collected and checked for signs of rat chews. The result was that none of the wax tags had been visited by rats.

This was great news! No signs of rat chews means it’s reasonable to conclude that while we know rats live in the coastal environments, they do not appear to be accessing the storm water network.

Another assumption that needed testing was around food waste. Would Miramar Peninsula restaurants, cafes and compost heaps pose a huge risk to the operation?

To understand this risk further, we initiated Operation Ratcam, a camera trial involving a number of food serving businesses and backyards with compost bins. The most striking result of this operation was how few rats and mice were seen over the three weeks the cameras were operational. Interestingly, the only rats that showed up on the cameras were in the chicken coop of our Project Director, James Willcocks and one in Dan Henry’s backyard (Predator Free Miramar community lead).

Although we didn’t capture many rodent images with this operation we were able to conclude that restaurants were a lower risk than initially thought, but rats in compost bins being fed regularly were a risk we would need to manage. To help mitigate the compost risk, our partners at Wellington City Council have been offering free rat proof compost kits for residents.

Improving our understanding about waste disposal on Miramar Peninsula (rubbish trucks etc) was our next challenge.

To get a better idea of what we were facing we interviewed several rubbish truck drivers about how they moved around the peninsula. We wanted to know whether full trucks of refuse were being parked on the peninsula overnight. We asked freight companies how goods were arriving on the peninsula and where was it coming from e.g. supermarkets?

These interviews were backed up by a business survey to understand the willingness of businesses to change their behaviours to minimise risks and reinvasion. The business community has been incredibly supportive of our project, and the majority of businesses have said they would be happy to change their waste management methods to help remove food sources for rats.

Before we could work out a proposed grid for our bait stations and traps on the Miramar Peninsula, we needed to carry out baseline monitoring to understand the depth of the problem and help answer some of our questions. Where are the rats? How do they move around the peninsula? Where are they most abundant?

The monitoring was done over three years by the Greater Wellington Regional Council’s monitoring team with help from Conservation Volunteers NZ and local community groups.

Community volunteers put out chew cards at 259 locations across the peninsula. The chew marks on each card were then analysed to estimate animal populations in the area.

The chew card survey helped us develop a baseline for the project, which will identify key problem areas and allow those involved to monitor progress each year.

Coastal areas were identified as the highest risk for reinvasion with rats and mustelids as they could exploit the cover of coastal vegetation and the concrete rip rap structure to travel through. Areas where rubbish dumping was an issue also needed to be addressed.

When working on a complex project like this, forewarned is forearmed. The better our knowledge of predator populations, the more effective will be our approach to eradicating them. This data has now been used to help us determine the best locations on the peninsula for trapping rats (and to place our devices). We also organised a clean up day with the community before we started the eradication to reduce rubbish dumping as a risk.

Despite its uniquely defensible location, we know the Miramar Peninsula’s western boundary is vulnerable.

The airport, Cobham Drive and Moa Point Road each provide rat runs into the peninsula, gaps which must be plugged if we are to get (and keep) the rat population at zero.

Before we can design barriers to prevent rats getting on to the peninsula we need to understand the pressure that will be applied by the volume of rats trying to pass through.

To gauge the scale of the rat population, Greater Wellington Regional Council helped us with another chew card survey.

Cards were placed at 100 metre intervals in a square roughly encompassing Evans Bay Marina – Maranui Surf Club – Onepu Road – Cobham Drive – Evans Bay Marina.

This survey revealed there are high rat populations in the coastal environment and this has influenced our eradication layout on the coast - a greater density of devices and an expansion of the coastal defences (barrier) along the coast and structures into the water to force the rats to swim if they want to get around.

All of the above work has helped us bring precision to the project. We have a good understanding of the risks and are able to mitigate them and be more confident of success.

There is a lot of learning happening on the peninsula and across Wellington that can be used elsewhere in the country. We are sharing this data publicly, enabling others to scale up and innovate. We are all in this together for the bigger goal of New Zealand becoming Predator Free by 2050.

In the early days of planning, we knew we needed unprecedented levels of support from the community for us to have a chance at making Miramar Peninsula rat, stoat and weasel free.

We would be putting out over 6,000 devices across the peninsula, working to a grid of 50m x 50m bait stations and 100m x 100m traps.

The bottom line is, we knew we couldn’t do this on our own.

For six months from January 2019 we had three full time field officers door knocking, speaking with residents, explaining our project and asking them to be involved.

It was a daunting task. Not many people enjoy having strangers knock on their doors uninvited, but fortunately our fears were allayed and our team were blown away by the positive response they received. An astounding 99% of residents were willing to participate and were happy for us to visit their property weekly. This was huge, and meant we could involve about every third household on the peninsula.

The motivation to become involved varied. Some residents were excited by the thought of having kākā, ruru, kārearea and lizards as common garden visitors, while others were just happy to have rats out of their homes.

We heard some wonderful stories from people who have lived on the peninsula for decades and who watched birds disappear as the pests increased, but are now gladly watching them return. Some have said they are thankful to see their grandchildren grow up in a place where seeing tui is now a normal part of everyday life. Others have watched the native geckos in their garden shed gradually disappear and want to make sure they are protected.

The support continues to grow and it’s not unusual for our team to be offered cups of tea when they do their weekly checks.

Importantly the community are our eyes and ears on the ground, letting us know straight away if they notice anything - turning our team of 30 into a team of thousands.

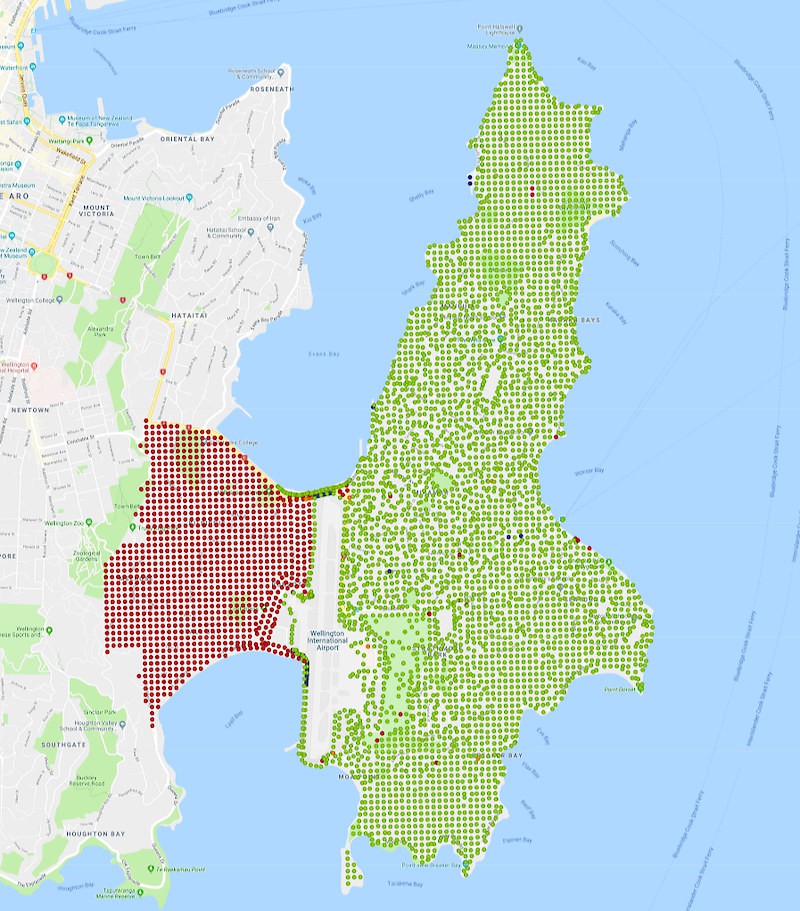

3000 permissions granted - every green dot is a trap or bait station that is checked weekly by our team.

The largest offshore island to be successfully eradicated of rats had a permanent human population of 120 inhabitants. Miramar Peninsula has 19,500 people and it’s not exactly an island.

Through it’s unique geography and thin land bridge (isthmus) connecting to the broader city, the Miramar Peninsula provides us with a unique opportunity to learn how we can safeguard urban areas after eradication and prevent reinvasion. This learning is critical as we step out across the city and broader project area.

Zero Invasive Predators (ZIP) have been designing and testing a prototype urban virtual barrier for us.

When developing a virtual barrier system in a city there are additional challenges that have needed to be considered such as major roading, cycle way and pedestrian development along Cobham Drive, an International Airport, homes and businesses. This has taken a lot of work to align many different stakeholders, understand their needs and incorporate them into a design that is functional and effective.

Unfortunately there is no easy single solution to keep the rats out. The virtual barrier system involves a number of different components that have been challenging to develop but have brought some incredible innovation to the fore.

The prototype design includes a short section of 80cm high fence running parallel with Cobham Drive and Moa Point Road to corral (or funnel) rats into clear areas where they will seek refuge in trap boxes. It will also include eight barrier lines of traps and bait stations across the neck of the peninsula complete with self reporting nodes to alert us if there are any catches, and automatic lure dispensers which release a small amount of mayonnaise daily to entice any rats. There will also be lines of traps extending along the coastlines as we know from our monitoring that rats, weasels and stoats like tracking the coastlines so this is a particular risk. The goal is to test how many lines of devices we need to intercept any potential invaders.

Of course, hard infrastructure (the barrier system) is just one element, we will ultimately be relying on Wellingtonians to keep us informed of any pest activity so we can respond accordingly.

We are also collaborating with research partners to help explore the unanswered questions we need to resolve. These include:

- Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research is helping us to develop proof of freedom modelling. Proof of freedom modelling is all about knowing when we get to zero rats, stoats and weasels. We use mathematical modelling to determine the probability we have hit zero, based on the data we are gathering throughout the operation. Manaaki Whenua are also helping us to better understand predator ecology in the urban landscape, including how far these predators move in the urban area, and therefore what density of traps and bait stations is needed to ensure every animal encounters one of our devices. All animals have a home range. In a forested landscape a female Norway rat’s home range might be 50m, but in an urban landscape these home ranges may differ. For example, if there is a rat in a compost bin getting a fresh smorgasbord of food everyday and he/she has a mate then maybe they don’t have to go very far at all.

- Victoria University students through the Centre for Biodiversity and Restoration Ecology are also contributing through collaborative research projects to develop new knowledge on the impact of predator eradication on susceptible native species such as geckos and skinks. There is lizard monitoring active in Miramar along the coast.

You’ll see in this video the rat managed to escape - they are very clever! In this trial, we tested a 90mm cap over the fence and found 1 in 10 rats could escape eventually. We then expanded the cap to a 110mm cap and were successful in containing the rats - success!

Wellington undertakes New Zealand’s biggest urban pest eradication, 8 July 2019.

Letter from Holden

We can learn a lot about ourselves, our city and the environment by connecting the dots looking backwards.

When local iwi talk about their whenua (land), their ngahere (forest) and wāhi tapu (sacred sites), they talk about a spiritual connection and about the mauri or “life-force” of these places.

As a descendant of the Taranaki tribes who migrated here in the 1820s, when I hear these stories I’m inspired to do my part to help bring back, at least in part, what our whenua and ngahere looked like so that we might again look after Papatūānuku (Earth) in a practical and tangible way.

I want my tamariki (children) and their tamariki to re-acquire that knowledge and kaitiaki role as cultural guardians of the forests, waterways and harbour here in Poneke (Wellington), in partnership with the wider community.

Not so long ago, Wellington’s inner harbour was forest clad, fed by multiple streams including the Kaiwharawhara, Kumutoto, Waikoukou, Waimapihi and Waitangi streams.

The latter formed a lagoon on the eastern side of Te Aro flats and was an important mahinga kai (food gathering place) for the Taranaki Iwi and Ngāti Ruanui inhabitants of Te Aro Pā.

Tuna (eels) were abundant in the kaiwharawhara and the forest around the inner harbour teemed with kererū and other native birdlife.

We can never return the landscape to what it once was, but I hope that as we get closer to our goal of being predator free, iwi become a partner in the project and help shape what range of taonga koiora (native species) we reintroduce.

I’d like to think that we could re-stock our pātaka kai, our traditional food reserves to the point where we could practise sustainable cultural harvest again right here in the city, in accordance with our traditional tikanga of kaitiakitanga.

The challenge will be to decide what we can realistically achieve in an urban environment and what range of vegetation and species can be returned.

Iwi will be involved in the planning of what the landscape might look like beyond predator free. Mana whenua will have certain aspirations around return of some culturally significant species and the ability to harvest them sustainably. It might be tuna, it might be kererū, it might be rimu timber for cultural use.

“Kia mauri ora rānō te whenua, kātahi ka mauri ora anō te tangata” - when the life force of the land is returned, so too will return the health and wellbeing of the people. Put simply - “heal the land, heal the people”

- Holden Hohaia, Taranaki Whānui Predator Free Wellington Ltd Board representative

Letter from Peter

Predator Free Wellington has had an impressive first year, things have gone better than we could ever had imagined, but it is important to remember we’re here to finish a job. We carry the mana of thousands of people who have been working away in this space for an incredibly long time.

Building on the existing work, we were able to bring in additional expertise and resources, we’ve achieved a new level of coordination and groundswell of support – and this is where the magic is happening. We are seeing Wellington rewild in front of our eyes. We are not having to wait generations to see the changes, they are happening now.

Together, we are responsible for people getting up earlier in the morning because of those pesky tui. There are more birds in our backyard gardens than ever before. The mauri (life force) is coming back!

Our focus for this year has been working to secure the exemplar of a predator free Miramar Peninsula. It is here we can establish a proof of concept before we look to scale the work across broader Wellington.

A proof of concept means we’ve demonstrated that our predator free goal isn’t a pipe dream – we can get to zero predators, have thriving biodiversity and communities, and scale up the model to deliver predator free across the broader cityscape.

We believe we can do this.

But right now, the biggest challenge is long term sustained investment. If we really want to do this we need to invest, as a community who share a cause.

On our team we have our partners Wellington City Council, Greater Wellington Regional Council, NEXT Foundation, Taranaki Whānui ki Te Upoko o Te Ika, Predator Free 2050 Ltd and tens of thousands of Wellingtonians.

We have baseline funding confirmed for five years, but we need to secure additional investment to scale up.

Once we have the investment needed we can look beyond Miramar Peninsula, out into the wider Wellington region and become the world’s first predator free capital city.

So we are inviting you to join our team. This is not only good for Wellington, but good for NZ, and good for the world.

“Naku te rourou nau te rourou ka ora ai te iwi” - with your basket and my basket the people will thrive.

- Peter Chrisp, Chair, Predator Free Wellington Ltd